Books

What I've been reading

The Incendiaries

R.O. Kwon

R.O. Kwon's debut novel is a story of religion and fanaticism at an elite college. Will Kendall is a lapsed evangelical who arrives at Edwards University and immediately falls in love with Phoebe, a Korean-American student. Phoebe in turn falls under the sway of John Leal, a barefoot proselytizer who supposedly was abducted into the North Korean gulag while doing missionary work in China. The story follows Phoebe and Will's relationship through her induction into Leal's cult and to a shocking act of violence. There are echoes of Emma Cline's The Girls, Donna Tartt's The Secret History and even Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club. I was also reminded of the story of John Chau, killed last year in the Andaman Islands while attempting to preach to an uncontacted tribe. The central question of the book is why Phoebe is susceptible, and Kwon suggests a few too many explanations for Phoebe's actions. We see Phoebe's childhood piano playing; her father's evangelical Christianity and her parents' tangled relationship; and even an uncomfortable relationship-rape scene between her and Will. Overall, structure of the novel is tight and suspenseful, and is an enjoyable and quick read.

January 1, 2020

Say Nothing

Patrick Radden Keefe

What a book. Patrick Radden Keefe's book focuses on a handful of characters involved in the Troubles in Northern Ireland: in particular, it focuses on Jean McConville, a mother of ten disappeared by the IRA in 1972, and Dolours Price, an IRA soldier. Radden Keefe's aim is to show that the past is both dangerous and close at hand in Northern Ireland. He demonstrates that Gerry Adams, the leader of the Sinn Fein party and hero of the Good Friday Agreement, likely approved McConville's murder. That breathtaking contradiction provokes a lot of questions about justice and what it means to reconcile and achieve peace.

Radden Keefe discusses the work of the journalist Ed Moloney, who wrote a book called The Secret History of the IRA in 2001, and later recorded hours of audio interviews with participants in the Troubles. Called the Belfast Project, it was meant to be a primary historical record of the period to be made available after the deaths of the participants. Remarkably, Radden Keefe never got access to the Belfast Project tapes, even though he had a strong relationship with Moloney. What's remarkable for me is that I read The Secret History of the IRA on a trip to Ireland in 2003 when I was 15; it's very cool to revisit the same issues fifteen years later and see how the history and politics have changed.

December 26, 2019

Play It As It Lays

Joan Didion

Didion's short novel came out in 1970, in between Slouching Toward Bethlehem and The White Album. In those collections of essays (discussed here on this page!), Didion is exploring the alienation of the 1960s. Play It As It Lays is the novelistic treatment of those same ideas. The book centers on Maria, a young actress floating through life in LA. Maria's husband is a top director in Hollywood, and her world is filled with affairs, vicious gossip, drugs, and benders. As with much of Didion's 1960s writing, the book feels very contemporary, treating subjects like homosexuality, drug use, and suicide in a matter-of-fact way that was likely shocking to its audience when it came out.

December 11, 2019

Last Boat Out of Shanghai

Helen Zia

History is taught as a series of settled facts and narratives: the Cold War was an inevitable consquence of World War II; a despot like Napoleon was inevitably going to step in after the chaos of the French Revolution. It is fascinating, then, to visit the seams in history where things didn't look inevitable: 1932 in Germany, 1945 in Yalta or Potsdam, or 1949 in China. Helen Zia's book follows four Chinese people who were swept up in the chaos of the Communist takeover. Her narrative covers some stories that have become stereotypes, like the engineer who wins a study visa to come to the US, but also some less-typical stories, like the boy whose father was a major figure in the Japanese puppet government in Shanghai during the war. While Zia's book doesn't fully explore questions of how people knew when to flee, it paints a vivid and engaging picture of the Chinese diaspora following the revolution.

December 5, 2019

There There

Tommy Orange

Tommy Orange's novel follows a wide cast of Native Americans as they prepare for a powwow in Oakland. Orange paints a vivid picture of the "urban Indian," a group that most Americans would regard as paradoxical and therefore invisible. I found myself thinking back to some of Sherman Alexie's work or to the Inuit film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Alexie was a mentor to Orange, and is thanked in the acknowledgments, but after several #MeToo accusations against Alexie, Orange asked him not to blurb the book. Orange's characters represent a wide variety of Indian experience, from the Alcatraz takeover of 1969-71 to powwow dancing, alcohol abuse, and intergenerational trauma. They're hopeful and misunderstood and sometimes desperate; Orange succeeds at humanizing a community that many readers don't even realize exists.

November 22, 2019

Someone to Love You in All Your Damaged Glory

Raphael Bob-Waksberg

I read this book on a flight to Tokyo, and I'm writing this review on the flight home, just over the International Date Line. Glory is a collection of short stories by the producer of BoJack Horseman, a show I've never seen, but know as an absurdist cartoon for adults. The book is funny in the neurotic mold of Woody Allen or Seinfeld, but aspires to the depth of George Saunders. Some stories feel like writers'-room gags, premises thrown out and built upon by a roomful of clever writers, but then they circle around and you realize you've read a portrait of an entire relationship, and it was never spelled out. The stories can sometimes feel closer to "Shouts and Murmurs" in The New Yorker than The Tenth of December, but still an enjoyable and light read.

November 10, 2019

My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Ottessa Moshfegh

My Year of Rest and Relaxation is a deeply weird exploration of a young woman's attempt to sleep for an entire year. It's 2001, just before the towers fall, and the unnamed narrator is floating in New York—both her parents have died, and she works at an art gallery after graduating from Columbia. She's lost, and approaches the world with a sardonic detachment. She's in a horrible relationship with an older man named Trevor, and has a single friend, Rita, who she treats horribly. Still, you can feel that she's seeking something, and beneath the cool-girl aesthetic is pain. She begins to see a psychiatrist who gives her an astonishing array of sleeping pills, and she embarks on her quest to sleep for a year. Moshfegh's genius is to give us characters who are unsettlingly sympathetic; in a plot where the narrator mostly sleeps, the tension between disgust and empathy propels the novel forward. The book is weird, almost experimental; even if it doesn't work all the time, watching Moshfegh work is fun.

October 25, 2019

The Other Americans

Laila Lalami

This is the second book of Lalami's I have read, and I liked it less than The Moor's Account, which I found startingly creative. Lalami is trying to write The American Novel of 2019; she's got urban artist hipsters and Muslim immigrants and Iraq war vets and resentful white male Trump voters. The book centers on Nora, a composer living in Oakland whose parents are Moroccan immigrants running a restaurant in the Mojave desert. Nora's father is killed in a hit-and-run, and the story unfolds in the aftermath. The pace is quickened by the suspense of the crime, but is otherwise digressive and quotidian. I read the book for a book club, and my friends pointed out that every character has something that "others" them—hence the title. The conceit sort of works, but occasionally flattens characters into their flaws—my friends imagined Lalami managing a spreadsheet of her characters' qualities. Still there's a quiet richness that made the book fun to discuss and fun to recall details with friends. Worth reading, but not at the top of the list.

October 12, 2019

The Right Stuff

Tom Wolfe

In 2015 the band Public Service Broadcasting released an album called The Race for Space, which tells the story of the Space Race via public domain recordings set to music. The title track sets Kennedy's famous Moon speech to a swelling chorus: the Brahmin accent quoting George Mallory, "because it is theah!" The last year has been full of space-race commemoration after the 50th anniversary of Moon landing, which still boggles the mind—leaving Earth, using completely analog equipment, traveling through space, landing on a different celestial body, and returning, safely. What I have learned in the last year is the tremendous cost of the project. For a time 5% of government spending was going to the space program.

All of which is preamble for Tom Wolfe's delightful history of the Mercury program, The Right Stuff. In the introduction, he's up front that this is a book about heroism and courage, which he points out is deeply out of fashion in military books. The title refers to the pilot's egotistical conviction that there's something innate to a pilot that keeps him calm in a crisis and able to control the wild machines being dreamed up by the US military. Wolfe's discussion of the X-plane program, which for a time was flying higher, faster, and farther than the Mercury program. The first Mercury astronauts were instantly lauded as brave heroes, but spent a lot of time among themselves worrying whether they were true pilots or simply passengers on rockets, no better than a chimpanzee sent up for science. Overall a fun and swashbuckling read.

October 5, 2019

The Overstory

Richard Powers

I struggled with this book. Powers writes a series of intertwined stories, where each character has a powerful relationship to trees. The book is really about the trees; the people act on behalf of the trees or through them, and they are constantly having mystical forest experiences. There is some beautiful writing here, but it is overshadowed by a thinly fictionalized account of the last fifty years of environmental radicalism. Powers dramatizes the history of the ELF arson at Vail and the story of Julia "Butterfly" Hill, who lived in a redwood for 738 days in the late '90s to protest logging. Much of that activism is noble and produced significant wins in timber management, but other parts of it indulge in environmentalism's misanthropic streak, which I have a very hard time with. Particularly disturbing is the public suicide of a character who has spent her life studying trees; while I believe that humans should take their place as one species among many, a belief system that leads to suicide as the only path to living harmoniously with nature is deeply wrong.

September 18, 2019

The Goldfinch

Donna Tartt

I resisted this book for a few years since I didn't love The Secret History. I was in college at the time, and the book's small-college setting felt too familiar, a symptom of the novelist's tendency to write about writers' workshops and universities. It was a happy surprise, then, when I raced through The Goldfinch. The novel is grand and sweeping; it's set in the present, but could easily be transplanted to the 19th century if you change a few details. The plot centers on Theo, a boy whose mother is killed in a terrorist attack at an art museum and who makes off with a priceless painting. The book meanders through Las Vegas, opioid addiction, and the art world, but throughout maintains confidence in the power of Art to endure and heal. Theo is an ambiguous character: Tartt does a lovely job of blending his mother's saintly qualities with his father's sins into a single compelling character. The book drags sometimes when the plot eddies into a corner and you begin to wonder how Theo will extricate himself, but each section is beautifully written.

September 11, 2019

Eileen

Ottessa Moshfegh

In a recent New Yorker profile, Ottessa Moshfegh describes her time in an MFA program at Brown:

"It’s a lot of mediocrity feeding on itself. So you better be radical, and you better hate everyone. Not that I did personally, but that I had to if I was going to protect the thing in me that I knew I wanted to grow."

The whole profile is worth a read (her partner comes to interview her for a literary journal and stays for two weeks), but I love the creative prickliness in the quotation. I've been meaning to read her since that article. Eileen is an uncomfortable book. Eileen, the narrator, is looking back at her youth in a dreary New England town (I pictured New Bedford). Her existence is horrible, with an alcoholic and abusive father and a job as a secretary in a prison for boys. The uncomfortable shift comes when you realize you are sympathizing too much with Eileen's sour point of view, and failing to call out the horror of her situation.

August 29, 2019

The Color of Law

Richard Rothstein

The Color of Law tells the story of government-enforced segregation in America, and it is an eye-opening history. As Rothstein writes, most people think of housing segregation as something that "just happened," created by countless private prejudices or the emergent action of racist real estate agents. Rothstein carefully demonstrates that in fact it was coordinated government policy that created our segregated communities. In particular, the Federal Housing Authority's refusal to guarantee mortgages to Black families locked them out of the postwar housing boom, effectively destroying several generations of wealth creation. As with many things chalked up to market forces, policy plays an outsized role in shaping the market, and behind the policy are very human politics.

August 17, 2019

The Wizard and the Prophet

Charles Mann

Charles Mann's book 1491 started as an article in the Atlantic, which I read as a freshman in high school. It was one of the first long-form articles I read and loved, and kicked off a lot of happy hours in the periodicals section at Loomis Chaffee. More importantly, it was an important corrective to the myth of an "empty" pre-conquest North America. That is a long preamble to say that I admire Mann as an environmental thinker and writer, and The Wizard and the Prophet is a terrific introduction to a central tension in the environmental movement. Mann draws a contrast between "wizards" who believe in technology to solve environmental problems, and "prophets" who believe in coordinated moral or political action. For the wizards, Mann profiles Norman Borlaug, the plant breeder behind the Green Revolution; for the prophets, he profiles William Vogt, a writer and ecologist. Like Mann, I identify with the "wizard" side of the question, and found his writing on Vogt to be less compelling. Still, this book would make an excellent text in an introductory college course, and it taught me some new ideas in a debate I've followed for years.

August 2, 2019

Conversations with Friends

Sally Rooney

A friend lent me Sally Rooney's first novel while I was on a camping trip in Sequoia National Park, and I read most of it one evening while camped at 9,000 feet. It's a better book than Normal People. The book focuses on two friends, Frances and Bobbi, and their slow entanglement with an older, glamorous, married couple, Nick and Melissa. Frances becomes involved with the husband, Nick (who is supposed to be impossibly worldly at 32), and much of the book focuses on the fallout from their affair. There are rich corners of character and relationship that go unexplored, like why the foursome connected in the first place, and what lies beneath Nick and Melissa's marriage.

July 5, 2019

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous

Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong is a poet, and his debut has the rich precision of poetry. The novel is structured as a letter to his illiterate mother, who emigrated from Vietnam in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. In it, the narrator, known only as Little Dog, describes his life growing up in Hartford, Connecticut, coming to terms with his sexuality, and becoming a writer. The book feels very much like memoir; I found myself thinking back to Educated repeatedly. The book is heartbreaking and beautiful: the narrator describes falling in love with a hardscrabble (and drug-addicted) farmhand named Trevor, abuse at the hands of his mother, and navigating the world as an immigrant. Particularly poignant for me were his descriptions of Hartford, since if the book is memoir, we were rough contemporaries there. I know the "C-Town on New Britain Avenue" that he describes, and the tobacco fields in Windsor, but they were far from my own upbringing. Highly recommended.

July 1, 2019

A Gentleman in Moscow

Amor Towles

I devoured this book in a single sitting on a flight. I initially resisted the book because it feels twee; it's the Grand Budapest Hotel version of Soviet history. And to some degree, that's true — the book glosses over the terrifying purges of the late 1930s and completely ignores the war, which was a cataclysmic event in Soviet history. Works like Lenin's Tomb by David Remnick, or the film The Lives of Others (about the East German Stasi) better capture the desperate claustrophobia and petty absurdism of living under Soviet totalitarianism. Still, there are parts of the book that work well: the way it captures the privilege of the Russian aristocracy (see also: Nabokov's Speak, Memory), the way the life sentence in a hotel resonates with a restrictive society. Overall a fun read.

June 23, 2019

Educated

Tara Westover

Educated, for those of you living under a rock, is a memoir of growing up in an isolated, survivalist Mormon family in Idaho. Tara Westover winds up as a history professor at Harvard, and her journey is extraordinary. The collision of fundamentalism and untreated mental illness is heartbreaking, as is the enabling of her family. Nothing about Tara's story is simple, but she tells it with an objectivity that makes it all the more forceful. As with any story like this, what she leaves out is equally interesting as what she decides to tell.

June 12, 2019

Normal People

Sally Rooney

Normal People is the story of Marianne and Connell, two teenagers in Ireland. The book traces their on-again, off-again romance through high school (where the posh Marianne is an outcast) to college (where the working-class Connell struggles to fit in). The first third of the book is arrestingly beautiful and surprising — Rooney has some lyrical passages about teenage love and social hierarchies. Unfortunately it's hard to figure out why they can't just decided to be together; the novel then bogs down with lots of angst and self-doubt.

June 9, 2019

The Broom of the System

David Foster Wallace

I bought this book at Shakespeare and Company in Paris while on a business trip; it felt fitting. David Foster Wallace wrote The Broom of the System while he was still at Amherst, and it was published when he was only 24. A later review described it as "like watching an 8-year old play Vivaldi with tears streaming down her face: beautiful, but a little disturbing." I've now read all of Wallace's novels (the others being Infinite Jest and The Pale King, finished after his death), and I used to say that I preferred his nonfiction, since at least he was tethered to the facts. In his fiction, his neurotic imagination really gets going. I think that was a glib take; one thing that struck me about Broom is how many of the themes and ideas would continue to pop up in both Infinite Jest and Pale King. Language, entertainment, the absurdity of modern work, boredom; you can see him wrestling with these ideas throughout his career. Broom is less mature than his later works, but it's also more exuberant. His references to Wittgenstein are pretentious, sure, but they're fun — this is a writer figuring out his powers.

May 30, 2019

The Mars Room

Rachel Kushner

The Mars Room is a book that sneaks up on you. It's the story of Romy Hall, a young woman entering prison for a life sentence for murder. Kushner grew up in San Francisco and spent months visiting a women's prison in California, and her affinity for both the state and the women she writes about is clear. There's a clarity to Kushner's writing that pulls you in and makes her characters deeply sympathetic. It's like she's researched so thoroughly that you stop noticing the research. The book has echoes of Orange is the New Black, but Mars Room is darker; the book can be funny, but doesn't make prison seem like an innocent ground for hijinks. Some of the book's most powerful moments are when Romy feels the existential despair of prison life, the way it completely robs a person of agency. After reading this and The Flamethrowers, I revisited The New Yorker's profile of Kushner, and found that it helped me understand her work even more fully. Telex from Cuba is on the list!

May 16, 2019

Sea People

Christina Thompson

I had finished half of this book before diving into The Great Believers, so I didn't actually read it in two days. Christina Thompson's history of the settlement of Polynesia is an engaging and evenhanded look at the very puzzling historical question of exactly how the tiny and farflung islands of Polynesia came to be settled. She discusses James Cook's 18th century voyages and the remarkable Tahitian navigator Tupaia; racist theories about how Polynesians were actually Indo-European; and the archaeological evidence that enables us now to date waves of migration with relative precision. My favorite section, unsurprisingly, was her account of the so-called voyaging movement, of which David Lewis's We, The Navigators (see below) was an early and critical part. Still, it was helpful to put his work in context and learn more about the cultural significance of the movement to Hawaiians and its rocky history, including the loss of Eddie Aikau after the capsize of the canoe Hokule'a in 1980. I loved reading about the early computer simulation work done at the University of London that proved that the voyages could not have happened by drifting alone. Ultimately a fun, if somewhat light, survey of Pacific history. It made me want to get in a boat and go exploring.

May 13, 2019

The Great Believers

Rebecca Makkai

Whew I loved this book. The best novels are both gripping and literary, and Believers is solidly in that category. The plot centers around Chicago's Boystown gay scene in the early years of the AIDS epidemic, and flips back and forth between the 1980s and 2015. A few years ago I read a lot about the AIDS epidemic—Randy Shilts'And The Band Played On; David France's documentary How to Survive a Plague—and it is strangely fascinating to read about events that just barely preceded your own lifetime and thus historical consciousness. The book focuses on a young woman named Fiona, who has recently lost her brother to AIDS, and her brother's friends, who are mourning him while losing one another to the epidemic. One of the book's narrators is a young gay man named Yale Tishman, and part of the power of the novel is how it puts you in his shoes, and makes you feel the terror and anger and shame and confusion of that time. In a wonderful subplot, Yale discovers a trove of WWI-era art, and Makkai makes the connection between the nihilist destruction of the war and the ruthlessness of AIDS; how they both destroyed and galvanized the creative community. Highly recommended.

May 11, 2019

House of the Spirits

Isabel Allende

For years, I counted One Hundred Years of Solitude as my favorite novel. I've read it twice, and probably am overdue for a re-read. I loved its grand sweep, its romance, and its use of myth to heighten its meaning. There are deep similarities between the two books, and I was a bit disappointed to learn that House of the Spirits was published in 1982, a full 15 years after Solitude. Still, there is enough richness here to recommend the book on its own. The women of the clan are the lifeblood of the book. Their clairvoyance, loyalty, and political righteousness animate the plot. Their masculine foil, Esteban Trueba, the patriarch of the clan, is a particularly complex character; he remains sympathetic even when his violence and mistreatment of everyone he loves has brought disaster on his family and his country. Beyond the characters, the plot is drawn from contemporary Chilean history. There is a famous poet who lives in a shiplike house on the coast, and a violent rebellion that leads to the death of a principled but ineffective President. Isabel Allende is the niece of Salvador Allende, and the plot coils and crumples toward the end after a languorous journey through the generations.

April 23, 2019

Black Leopard, Red Wolf

Marlon James

In a review of Black Leopard, Red Wolf for NPR, Amal El-Mohtar writes,

Reading Black Leopard, Red Wolf was like being slowly eaten by a bear, one inviting me to feel every pressure of tooth and claw tearing into me, asking me to contemplate the intimacy of violation and occasionally cracking a joke.

The book is extraordinarily violent, and proceeds with the same dizzying density as James' A Brief History of Seven Killings. In a recent profile in The New Yorker, Jia Tolentino explored James' struggle to embrace his homosexuality in spite of a conservative religious upbringing in Jamaica, as well as his interest in African history and myth. Both strands are present in the book, with the mythical geography loosely based on historical African cultures and a lot of violent sexual imagery. Although I am interested in his Afrocentric take on fantasy and enjoyed some of the mythological elements of the book, overall I found the book hard to read.

April 16, 2019

The Flamethrowers

Rachel Kushner

I finally got around to reading Rachel Kushner! And what a novel. The Flamethrowers centers around Reno, a young artist swept up into the chaos of 1970s New York. Reno is a wonderful, complex character, a three-dimensional woman who is ordinary enough to be believable. She falls into a relationship with Sandro Valera, the scion of a powerful Italian industrial family, and ends up in a spectacular crash while speed testing a Valera motorcycle on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Kushner references Italian Futurism and Land Art and the 1977 blackout; somehow all of these strands weave together into a rich and complex novel.

March 10, 2019

Reinventing Bach

Paul Elie

One of the perks of my apartment is that my upstairs neighbor is a cellist; I can hear her practicing as I write. It is a fact of my life that I am much more talented at being interested in art than I am at actually making it, and so after she and I discussed Bach one day, she recommended this book. To my surprise, Elie focuses on recordings of Bach, particularly those by Albert Schweitzer, Pablo Casals, and Glenn Gould. The remarkable thing is that Spotify has many of the recordings mentioned in the book, so I would listen to Schweitzer's early 1935 recording of Bach's Toccatas, made in a 900-year-old church in London on the eve of the Second World War. Elie's descriptions made the listening experience much richer because I could hear what Schweitzer was putting into his playing. He describes how Gould made the recording studio an instrument, and how Casals used music to lodge a decades-long personal protest against the Franco regime in Spain. I have also been listening to several music podcasts ("Switched on Pop" and "Song Exploder," particularly), and what I love is the way music combines engineering with art, analysis with creativity. An A is 440 Hz, but that doesn't explain why we feel something when we listen to Bach's Chaccone. The book is less successful in its biographical treatment of Bach's life, but worth it for its explanation of some beloved recordings.

February 18, 2019

Speak, Memory

Vladimir Nabokov

Speak, Memory is Nabokov's autobiography. It covers the years between his earliest memories in 1903 (he was born in 1899) through his departure for the US in 1940. I find Nabokov endlessly fascinating: English was his third language after Russian and French; his long, rambling road trips with Vera through the US in the '50s; his obsession with butterflies. The pleasures of Speak, Memory are twofold: first, the historical interest of a life lived across the cataclysms of the 20th century, and second, the astonishingly beautiful writing. Nabokov's family was prominent, as his father and grandfather served in the Tsar's government. They lived in mansions in St. Petersburg and decamped for a country estate in the summers. In many ways, prerevolutionary Russia was still feudal, and Nabokov's family was on the right side of society. It is poignant to consider how wrenching modernity would be for Russia— with progress would come unimaginable horror.

As an aside, Nabokov's vocabulary is immense. Below are the words I scribbled into the frontispiece and looked up later:

palpebral: adj, relating to the eyelids

fatidic: adj, of or relating to prophecy

blackamoor: n, a black person

frass: n, fine powdery refuse or fragile perforated wood produced by the activity of boring insects

aquarelle: a style of painting using thin, typically transparent, watercolors

xanthic: adj, yellow

ecchymotic: adj, bruised

enuretic: adj, relating to wetting the bed

refulgent: adj, shining brightly

nictitating: v, blinking

quiddity: n, the inherent essence of someone or something

purblind: adj, having impaired or defective vision; dimwitted

nankeens: n, a yellowish cotton cloth; pants made of nankeen

cacologist: n, one who has a bad choice of words or poor pronunciation

zoolatry: n, the worship of animals

shantung: n, a dress fabric spun from tussore silk with random irregularities in the surface texture

oasal: adj, of or relating to an oasis

chamfrained: adj, wearing the head armor of a horse

persiflage: n, light and slightly contemptuous mockery or banter

inanition: n, exhaustion caused by lack of nourishment

drisk: n, a drizzly mist

January 20, 2019

The Better Angels of Our Nature

Steven Pinker

Occasionally, usually without intending to, my reading takes on themes. A few years ago there was a series of novels that took on race in America; another time it was the War on Terror. The last few books I've read have been about the human capacity for cruelty. Pinker's book is the broadest of them all. His project is to show that over the last two thousand years, violence has declined precipitously. The first half of the book is an exhaustive sociological survey of death rates by violence (expressed per 100,000 people) and an exploration of the forces that have made that rate go down. The second half is a psychological and evolutionary exploration of humanity and how we are capable of both cruelty and grace. I appreciate Pinker's rigorous style; he stays close to the data and debunks many of the sillier claims about human nature. Pinker is an Englightenment liberal, in the classical sense, and he explains the various strains of Enlightenment and counter-Enlightenment thought in a clear and cogent way. The book is rich and fascinating and is a feast for further thought: the roots of the Holocaust, the surprising uptick of violence in the peace-and-love '60s, and the statistical likelihood of a third World War. If there's a gap in the book, it's about European colonization — while the violence was more indirect (famines instead of wars), it still killed an enormous number of people. Overall, eye-opening and rigorous, and fundamentally optimistic.

January 2, 2019

Bury the Chains

Adam Hochschild

Hochschild is one of my favorite writers; this is the fifth book of his I've read. He's a classic human-rights liberal — he was a founder of Mother Jones, and his histories focus on popular movements like anticolonialism (King Leopold's Ghost), resistance to the First World War (To End All Wars), and resistance to Fascism ( Spain in Our Hearts). Bury the Chains is solidly in that vein as the story of the British movement to end the slave trade in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hochschild paints a vivid portrait of the contradictions of Enlightenment England. It was a deeply religious era, but one making great advancements in science. It was a time of cruel punishments and harsh working conditions, but also of cosmopolitanism and expanding literacy which led to more humane perspectives. The heroes of Hochschild's narrative are a small group of Quakers, Anglican clergy, and politicians who carefully documented the atrocities of the slave trade and brilliantly activated popular resistance, including now-familiar tactics like boycotts, petitions, and direct mail. The way they moved public (and political) opinion from slavery as a distasteful but inevitable fact of life to an unacceptable moral outrage is an inspiring lesson.

December 23, 2018

The Making of the Atomic Bomb

Richard Rhodes

Rhodes' book opens with the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard stepping off a London curb and having a vision — inspired by an HG Wells novel — of atomic weapons. The book then traces the thirty-year project of theoretical insight, painstaking experimental research, and finally military-industrial achievement that produced the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As I read the history I reflected on three ideas: first, that the race to build the bomb was the last time that science was seen as "Progress" and as an unalloyed good. The aftermath of WWII and the recognition of what industrial "Progress" had wrought — from the Holocaust to the bomb — would rightly give rise to political critiques of industrialism, as in the environmental movement. The second idea is the aesthetic of the "atomic age," with its mushroom clouds and control rooms. Rhodes' description of the first Trinity test, held only three weeks before Hiroshima, is extraordinary for its otherworldliness. Finally, I was struck by the prescience of purpose and pace of development. The physics community knew they could build a bomb almost as soon as the war started. Most of the work was scaling up industrial processes; they went from isolating a few micrograms of plutonium in 1943 to creating several pounds of it for a bomb in 1945.

December 15, 2018

The Shell Collector

Anthony Doerr

Doerr is rightfully famous for his novel All the Light We Cannot See, and this remarkable collection runs over similar concerns as the novel. Doerr's characters have rich internal lives, vivid relationships with nature, and often, some characteristic that holds them apart from the world. The first two stories in the collection are some of the best I've ever read — in particular the title story, about a blind shell collector who inadvertently discovers a miracle cure in a toxic snail, and in "The Hunter's Wife," about a taciturn Montana hunter and the mystical powers of his wife. Highly recommended.

November 25, 2018

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet

David Mitchell

Thousand Autumns is the third Mitchell novel I've read, after Bone Clocks and Cloud Atlas. It has a similar ambitious sweep as the previous books, but is more grounded and less sci-fi. Cloud Atlas remains my favorite of his work, but I enjoyed this book quite a bit. The story takes place in the late 18th century in a Dutch trading outpost just off the coast of Nagasaki. The title character is a decent and ambitious young Dutchman who has traveled to "the East" to seek his fortune and earn enough to marry in the Netherlands. He gets tangled in a complex story of corruption, imperial geopolitics, and the internal politics of Japan during the Shogunate. Japan was famously hostile to outsiders until it was forcibly opened to trade in 1854, and Mitchell does a serviceable job of writing about Japanese characters and their culture during that era.

November 22, 2018

The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility

Stuart Brand

I've wanted to read Stuart Brand for a while now, but never got around to it. He has a very Northern-California sensibility as a thinker, since he's a futurist and a technologist as well as an environmentalist. That separates him from some others in the environmental movement, who see technology as primarily a threat to the natural world. The book was published in 1999, right at the height of hype about "the Net," and the book is littered with references to dot-com era figures like Jaron Lanier and Brewster Kahle. The book is a series of meditations on what it means to hold a very long perspective — Brand suggests 10,000 years. It's an elegant way to force ourselves to consider both stewardship of resources and the folly of many of our pursuits. One of the most useful ideas in the book is a diagram showing the relative rates of change of societal forces: Fashion changes most quickly, followed by Commerce, Infrastructure, Governance, and finally, Nature.

November 19, 2018

Outline

Rachel Cusk

I bought this novel thinking it was by Rachel Kushner, not Rachel Cusk. I'd read a profile of Kushner and was interested in her work, but so it goes. My misunderstanding made Outline more interesting, especially after the fact; I had to recalibrate my understanding of the book. The novel is quiet and intelligent, the kind of book you're not completely sure you've grasped after the first read-through. The narrator, a novelist, is unnamed, and she reveals herself to us only through the reflection of her conversations. In that way, the title functions on a few levels: we see the narrator faintly, as in a visual outline, and we see only the outline of her story, as if it is an unfinished novel.

November 10, 2018

Barkskins

Annie Proulx

A 700 page novel about the magisterial sweep of the colonization of North America and its ecological legacy? Yes please. The book traces two French indentured servants who wind up in New France in the 1600s, following their descendants all the way into the 21st century. It weaves together ecological and political history; I found myself thinking often of Bill Cronon's Changes in the Land or Nature's Metropolis. My only disappointment was that by the end we were racing through generations, but overall a fun and broad read.

October 8, 2018

Never Lost Again

Bill Kilday

Another book about maps! The genesis of Google maps came from two startups acquired by Google: a team of 30 called Keyhole, that built what we know as Google Earth, and another, called Where2Technologies, which had only four people and contributed some of the core technology for the smooth, fast "slippy" maps we use today. Kilday was the head of marketing at Keyhole, and his biases, toward his original team and to marketing, are evident. Still, it's an eye-opening look at how recent digital mapping technology is. Some of the product decisions they made then, like being inspired by the Eames film Powers of Ten, still shape how we view maps on the web today. Google made the acquisitions after seeing that 25% of web searches had a geographical component; location matters!

September 30, 2018

A Widow for One Year

John Irving

It's been a few years since I've read an Irving novel, and it was fun to come back. The story revolves around grief, sex, infidelity, and a spectacularly dysfunctional family, but manages to be warm and funny at the same time. Ruth, the daughter, is an especially three-dimensional character, and the way the story plays out across the generations is satisfying.

September 28, 2018

The White Album

Joan Didion

The White Album's title essay famously opens "We tell ourselves stories in order to live," and this volume is Didion's second attempt to make sense of the Sixties. Published in 1979, it's the followup to Slouching Toward Bethlehem, and overall the book is looser; there's less of a sense of mission to what she's trying to say. "The White Album," the essay, details a psychiatric episode, and you get the sense that her own crackup mirrors the country's. Her essays about feminism are nuanced and arch, and her treatment of California adds depth to a place that often feels quite shallow, historically.

August 26, 2018

My Struggle: Book 5

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Book 5, subtitled "Some Rain Must Fall," felt different than the rest of the My Struggle series. It's more novelistic and less automatic; the book is more of a traditional narrative than the tight, intensely felt vignettes of the earlier books, and the pacing dragged more than the others. Perhaps that's intentional — it covers a long period of creative frustration, self-destruction, and self-doubt in Karl Ove's life. There are parts of the book that are almost frightening, like when he hurls a glass at his brother in a drunken rage or cuts himself soon after meeting a woman he would later marry. Still, you root for him. I was surprised to find out that I've caught up: Book 6 will be released in late September, and weighs in at a staggering 1200 pages.

August 19, 2018

Scale

Geoffrey West

Every once in a while, a nonfiction book comes around that turns my thinking upside down, and I'll be adding Scale to the list (Others include Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond and The Information by James Gleick). West is a physicist, and he uses the theoretical tools of physics to look at biological and human systems. The core idea of the book is that universal physical laws emerge from the ruthless optimization of evolution, which gives us predictive power. For example, every mammal gets about 1.5 billion heartbeats; a mouse just churns through them much faster than an elephant. Further, there's a literal economy of scale for the elephant — its cells sustain much less damage than high-intensity mouse cells, and so it lives much longer. The book is full of cool insights, like the fact that if you could bundle up every leaf stem on a tree, the area of the bundle would equal the cross-sectional area of the tree trunk. The later chapters, about companies and cities, are a bit more speculative, but suggest an ecology of human systems that could be incredibly powerful.

August 10, 2018

My Struggle: Book 4

Karl Ove Knausgaard

A lot of the critical discussion of My Struggle centers on how quotidian it is; the series is usually described as "both tedious and gripping." The description implies that the book is a diary, or an exhaustive account of Knausgaard's days, which isn't quite right. Each volume centers on a discrete period in his life, and on a discrete and illustrative set of events within that period. There's a substantial amount of artistry and storytelling to create the combination of "tedious and gripping." Volume 4 recounts Knausgaard's year as a teacher in a small town in northern Norway. He learns how to be an adult and furiously trying to become a writer. The mistakes of early adulthood are grand and painful, and he's no exception. It's cathartic to relive them through his writing.

July 28, 2018

My Struggle: Book 3

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Book 3 of the My Struggle series, subtitled "Boyhood," is set across Karl Ove's childhood. There's less self-awareness; kids don't know a lot, and he captures what it feels like to slowly learn more about the world. He learns about girls, and sports, and mischief, and social taboos. One of my favorite works about childhood is Where the Wild Things Are — something both the book and the movie get right is the volatility of being a kid. While "Boyhood" is much less whimsical, it put me right back into the drama of growing up. Book 4 is on order.

July 6, 2018

Prisoners of Geography

Tim Marshall

I'm sorry to say that this book is not very good. It seemed promising: a bestseller focused on geography and maps, that uses the natural world to explain geopolitics. Unfortunately it was superficial and light, and in each chapter I found myself thinking back to other books that took on the similar material in much greater and more interesting depth.

June 24, 2018

My Struggle: Book 2

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Well, I think I'm hooked. The second volume is subtitled A Man in Love and with any of Knausgaard's titles, there's irony: the book focuses mostly on the tensions and contradictions of being a middle-aged parent rather than the rush of romance. Children are both maddening and meaningful; he explores both the power of the experience and the toll it puts on his career and on his marriage.

June 22, 2018

My Struggle: Book 1

Karl Ove Knausgaard

I've been curious about My Struggle for a few years, but always felt too daunted to dig in. The weirdly Hitlerian title, the Scandinavian seriousness, and the prospect of embarking on a 3,600 page autobiographical project made it hard to start. The books are often tedious, but still gripping; the power comes from a sense of identification with his inner monologue. Knausgaard manages to capture what it feels like to be a thinker and an observer of your own life.

June 5, 2018

Purity

Jonathan Franzen

I was not terribly impressed with Purity. It's a fast read, and fun and suspenseful at times, but I kept wondering if it would attract attention if not written by Franzen. The plot centers around a plucky young woman (the eponymous Purity, aka Pip) who gets involved with a mysterious transparency organization similar to Wikileaks. The book is supposedly centered around Pip, but ends up examining a complicated relationship between men, and the book's female characters felt incidental and light.

May 8, 2018

Native Son

Richard Wright

Native Son was sitting on a free paperback cart as I boarded my flight from Boston to San Francisco last week, and I read it on my flight home. The novel directly takes on the claustrophobic feeling of being an urban black man in the 20th century in a way that I found surprising compared to other books of the era, and I found myself reading the book for its politics more than its literature.

May 1, 2018

Oblivion

David Foster Wallace

This book made me sad. David Foster Wallace is one of my favorite writers, but I've neglected his short stories (still to read: The Broom of the System and Brief Interviews with Hideous Men). Oblivion was published in 2004, only a few years before he killed himself in 2008. The stories have his usual frenetic pace and vocabulary, but where that pace feels fresh and intelligent in his other work, it's harder to see its purpose here. There are the typical themes of bureaucratic ennui and meaninglessness, but the stories are somehow sadder and less compassionate to their hapless characters.

April 30, 2018

White Tears

Hari Kunzru

White Tears is a novel about race and music, and I devoured it in an evening. Two young men start a record label devoted to unearthing old Black music, and they discover some very dark realities. It's a gripping thriller (in fact tips into horror, at points), but is ultimately light on historical resonance, mostly because its black characters are thin caricatures, or villains. The book owes a lot to Invisible Man; I found myself thinking back to high school, when I discovered Louis Armstrong's "Black and Blue".

April 27, 2018

Footsteps

Various Authors

Footsteps is an anthology of New York Times articles that trace the footsteps of famous authors. Abbey gave me the book for my birthday. I'd never read the feature in the paper, but I loved this book. I learned things about authors I knew very little about: Rimbaud never wrote poetry after age 21, died at 37, and lived for a long time in Ethiopia. Who knew! I read the book on a business trip to Berlin and learned that Isherwood lived near the office; I hadn't known that Mark Twain had written about Hawaii for the Sacramento Union. Each piece has a unique angle, so they never get repetitive. It's a rare book that manages to be intellectually stimulating yet still light.

March 10, 2018

Embracing Defeat

John W. Dower

Embracing Defeat focuses on the years of American occupation, from 1945-1952, and examines fascinating questions of societal transformation, moral responsibility for catastrophe, and hard compromises for the victors following capitulation. For every radical decision (disbanding the zaibatsu, writing pacifism into the Constitution), there were equally conservative decisions (retaining the Emperor, most conspicuously). The interaction of the Japanese response to defeat and American policy choices forged modern Japan, and the book is an indispensable guide to the period.

February 1, 2018

We, The Navigators

David Lewis

David Lewis spent 5 years in Polynesia learning from the last of the traditional navigators, and he collects his research in this tremendous monograph, now in its second edition. It's an academic book, so can be a bit dry at times, but his methodical approach is welcome for its comprehensiveness. While Western navigators (before GPS) would attempt a sun sight once a day, and then fix their position on a static map, for the Polynesians, navigation was a continual process of integrating observed data into a picture of their location. And what a rich set of data it was! There's the "sidereal compass," or the position of stars on the horizon as they rise; navigating by judging the refraction of swell around islands in order to expand the "landfall target"; learning the homing behavior of birds 20 miles offshore; or most remarkably, using deep-sea phosphorescence to detect islands up to 80 miles away. Reading Lewis's account of his voyages made me want to go offshore in the South Pacific or at least become a much closer observer of natural phenomena in my backyard.

December 16, 2017

Pinpoint

Greg Milner

This is a fun book, and not just because I have a professional interest in GPS technology. It's an engaging history and an approachable but sophisticated technology explainer. The history of GPS winds throught the Cold War, the "smart bombs" of the Gulf War, and finally exploded into civilian applications in the late '90s. Milner dives into a number of fascinating side-subjects, from Inuit navigation in the far north to how GPS turn-by-turn changes our minds to geodesy, or the study of the shape of the Earth.

December 9, 2017

Fates and Furies

Kate Groff

Fates and Furies lives up to its title. One reviewer described Groff as "writing as if her hands are on fire" and the book's twisty plot reminded me of Gone Girl. There are some thin spots, particularly in the extremes of the characters: cartoonish villainy, unlimited money, unlimited charm, unlimited anger. But overall a fun, literate, and fast-paced read which offers some complex thoughts on marriage and art.

November 25, 2017

Moonglow

Michael Chabon

Michael Chabon's characters are usually bright, and loud: the superheroes of The Adventures of Kavalier and Klay or the Jews at the end of the world in The Yiddish Policeman's Union. In Moonglow, he's still dealing with his themes of Judaism, literature, and complex families, but the book is much quieter. The book is a fictionalized account of conversations with the narrator's grandfather; the narrator is also named Michael Chabon, and the book is propulsive but not suspenseful. It's a novel, with a novel's elegant plotlines, but retains the circumstantial revelations of memoir.

October 11, 2017

Slouching Toward Bethlehem

Joan Didion

Didion's book of essays is billed as an examination of "the atomization of modern life." All the essays in the book were written between 1961 and 1967, and reading them now is both an exercise in history—since she is writing for a contemporary audience—and in reflection, since in many ways it feels like "the center cannot hold" in 2017 America. My favorite essays are the title essay, about the hippies of the Haight, and "On Keeping a Notebook," which is about what it means to observe the world as a writer.

September 23, 2017

News of the World

Paulette Giles

A light, lovely Western. Set in Texas in the 1870s, it tells the story of an old man returning a girl, recently recovered from captivity by the Kiowas, to her family. Not nearly as gritty as Lonesome Dove; it manages to be sentimental without cloying.

September 18, 2017

The Caine Mutiny

Herman Wouk

A classic World War II novel that won the Pulitzer Prize in 1952. The book celebrates old-school virtue, but retains just enough ambivalence about war to be interesting. Many passages about the terrible leadership of Captain Queeg reminded me of Trump, in that cultivating loyalty and good faith is much more likely to yield results than mean-spirited tantrums.

September 11, 2017

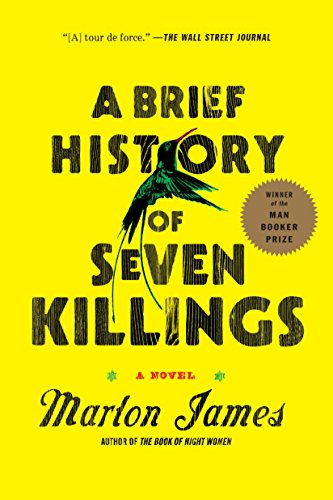

A Brief History of Seven Killings

Marlon James

A Brief History tells a winding and fragmented story, loosely centered around the 1976 shooting of Bob Marley in his home in Jamaica. The book is violent and hard to follow, with multiple narrators speaking in multiple dialects, but I learned a lot about Jamaica in the '70s. The book won the Man Booker prize in 2015, beating out a strong shortlist, including Hanya Yanigihara's A Little Life (which I have read) and Sunjeev Suhota's Year of the Runaways (which I have not).

September 6, 2017